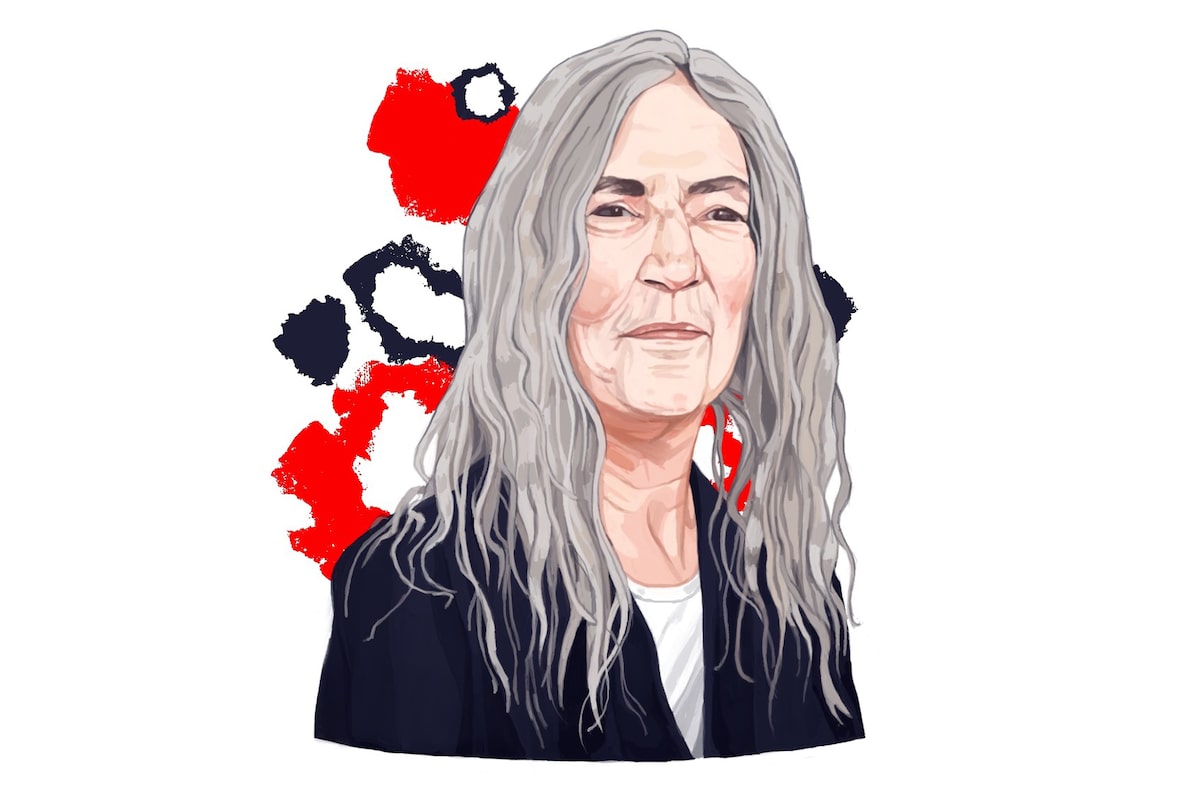

Illustration by Ashley Floréal

“She comes around here / At just about midnight” − Gloria, written by Van Morrison

At the end of our video call, Patti Smith asks what’s on the wall behind me. “I’m really curious about that photograph,” she says.

It’s a basketball card from 1972 of Pete Maravich, the shaggy, flamboyant point guard for the Atlanta Hawks.

“It’s small, but with a wide mat,” she observes. Smith, a Polaroid enthusiast as well as poet, rock ‘n’ roll singer and songwriter, is less concerned with the basketball player than she is with the card’s presentation.

With her, it’s all about the framing.

Smith, 78, has a new memoir out. The storytelling in Bread of Angels is dreamy and impressionistic, with the author self-portrayed as a writer who happened into poetic art-punk stardom.

To songwriters, the City of Angels is a little bit heaven and a little bit hell

“There was no plan, no design, just an organic upheaval that took me from the written to spoken word,” she writes of her musical beginnings.

Smith burst into public consciousness with the release of her debut album Horses in 1975. The record produced by the Velvet Underground’s John Cale famously began with a stark reimagination of Van Morrison’s Gloria, first recorded by Morrison’s band Them in 1964.

That she was a woman singing about another woman was a message. “I chose to open with our version of Gloria, claiming the right to create, without apology, from a stance beyond gender or social definition, but not beyond the responsibility to create something of worth,” Smith writes in Bread of Angels.

The album cover is iconic: An androgynous, unsmiling Smith with a jacket casually slung over her shoulder, shot in black and white by her friend Robert Mapplethorpe. The vibe is half-Baudelaire, half-Sinatra.

Hyper-attentive to her image, Smith even wrote the ad copy: “three chords merged with the power of the word” soon became quoted as much as her lyrics.

Smith went on to record 11 studio albums, none since 2012’s Banga. She’s released as many or more memoirs, as well as books of poetry and photography. The punk-rock matriarch spoke to The Globe from New York.

You write that in sequencing Horses, you wanted to present the illusion of a cinematic experience. With this book, it feels like you’ve done the same. Was it intentional?

Thank you. I’m a very visual person. I remember things as if they are little films. And I have a very good memory.

The stories about your childhood are particularly vivid, almost like fairy tales.

Well, I had two siblings who allowed me to be the storyteller. When we were being punished or it was raining or we all had measles together, I told stories. Often, they were our own: “Tell us again how you beat up Jackie Riley, the neighbourhood bully.” My brother died young, but my sister and I still relive these stories. They’re very alive in my mind, more than any other period in my life.

You were often bedridden with illnesses.

It was just after the Second World War. There were a lot of sickly children. I got tuberculosis because I was watched by a Polish woman with six children. We all got sick. The whole neighbourhood had mumps and measles. I caught a lot of contagious diseases because I was born with bronchial pneumonia. To this day, I have chronic bronchitis.

You read Peter and Wendy while you had the mumps. Being isolated, do you think you lived in your head more than most children?

Being in bed wasn’t so bad for me. I was often quarantined but when you’re a kid, you don’t take illnesses personally. I could read for hours and make up little stories. They were sort of mystical times.

From 2012: Patti Smith: The responsible artist

How so?

Fever dreams, slight hallucinations. It was a little strange. I do believe it all nourished the creative side of me. I had long talks with the writer William S. Burroughs about that in my 20s. He had scarlet fever as a child. He believed it helped him as a writer.

When asked if anything good came from his childhood polio, Neil Young said, “walking.”

Well, I bet if you talked to Neil he would have other things to say about how his illness manifested in his work and his compassion for others.

Do you know him?

Yes, but I didn’t know he suffered from polio. There are aspects of Neil that are so hyper − his compassion, his understanding of things, his range. I’m sure having to suffer as a kid had something to do with that.

You moved around a lot with your family while growing up. You seemed to have a strong sense of curiosity, even fearlessness.

I have a certain amount of fearlessness in terms of work, and when I had to take care of my siblings. But I’m not a big adventurer. I don’t swim. I never went mountain climbing. I haven’t been to a lot of exotic countries. I don’t even know how to drive.

You rode the Cyclone roller coaster in Coney Island, N.Y. I feel like that’s the rare experience we have in common.

Believe me, you have to be a little fearless to do that. That was quite a ride. I had come off an accident. I had a neck brace for six months.

From falling off the stage, opening for Bob Seger in 1977.

Yes, and the reason I went on the roller coaster was that I was being hesitant. I was always a very abandoned performer. My pianist, Richard Sohl, who I really loved, noticed I was a bit self-conscious onstage after my accident. He thought it was time for me to break through that. Getting on the roller coaster was his idea. After that, everything seemed easy.

Patti Smith performs at The Met in Philadelphia in April, 2019.Owen Sweeney/The Associated Press

Do you have an onstage persona?

I don’t, except that I’m not very social when I’m offstage. But when I’m onstage, of course, when I’m speaking to 10,000 people or 10 people, I’m communicating with them. I don’t do any preparations, though. I wear the same clothes offstage and on. I just go up, do my job and leave.

Were you a different performer when you were younger?

I’m not as aggressive now, physically. I’m older − 50 years older. I think I’m as strong a performer as ever, though.

Indie-rocker Meg Remy, of U.S. Girls, recently said true rock ‘n’ rollers are sweethearts offstage, grappling with the complexities of life. But onstage, they crystalize that into something that is an armour. Does that resonate with you?

I can’t say I’m so sweet offstage [laughs]. But the way I am with you right now is the way I am onstage. I never had any desire to be a singer or a performer or make records. I always wanted to be a writer or a painter.

Do you ever experience stage fright?

No. And when I get off the stage, I don’t feel like I’m a god or something. I don’t feel like a god onstage, either. It’s my job. Whatever crazy things happen onstage, it’s my job is to stay in communication with the people.

I think fans see you as a rock goddess.

Probably not now [laughs]. I was more goddess-like when I was younger − a scrawny goddess. I didn’t aspire to those things, though. With my first record, Horses, I wanted to merge poetry and rock ’n’ roll and give voice to people like me who are sort of mavericks and outsiders.

You write that after making Horses, you thought your job was done.

I did the second album, Radio Ethiopia, because I had a loyal group of people and I liked working with them. My brother was the head of my crew. I had a loyal band. And I liked travelling, but I never had enough money to travel. Being able to tour gave us all an opportunity to see the world.

But that lifestyle isn’t conducive to writing, which you say was, and is, a problem.

It really is counterproductive. Making records and touring is external, collaborative. Writing takes solitude. You have to be able to work on your own. You have to sit and think for hours or edit something that might take days. And I didn’t have that kind of time or that kind of solitude. So, it was a conflict, and it’s always been a conflict.

So, why do it? You recently completed a 50th anniversary Horses tour.

Yes, and I feel that part of my life has come to an end.

Don’t you have European dates booked for the spring and summer?

But not with a big band. I won’t be doing that any longer. I have a smaller band, a quartet. We do a lot of work in Europe, but it’s a smaller show and the tours are shorter.

Does Patti Smith, the writer, enjoy being Patti Smith, the performer?

Being a performer is a good thing, but it doesn’t make you better than anyone else. What I am is a good survivor. That’s what I do best.

This interview has been edited and condensed.